A place of discovery

Growing an industry

At Te Papa Tipu Innovation Park here in Rotorua, Scion’s research has spanned 75 years and has taken us on a journey from soil to space.

At the time of the first large scale exotic forestry plantings in the 1920s, little was known about how to grow trees as a crop. This spurred research that continues here in Rotorua today. Our researchers devised methods for propagation, planting and silviculture (forest growing) that influenced plantation forestry practices throughout the world.

Selecting the best

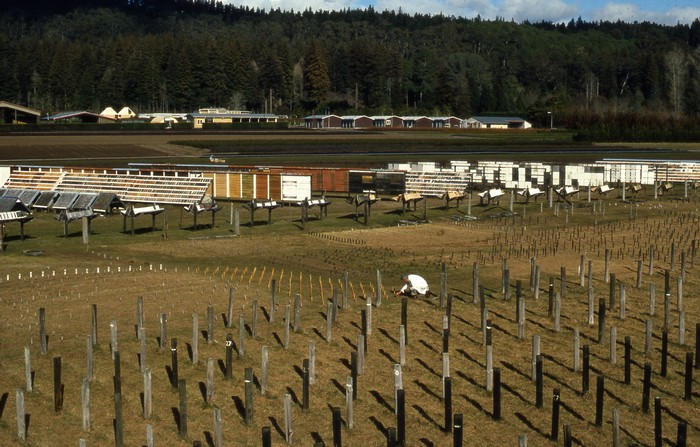

Tree breeders began improving the quality of forests by selecting seed from trees with desirable characteristics. The first radiata pine seed orchards were established in the 1950s. Since then, there have also been tree improvement programmes for cypresses, eucalypts and Douglas-fir.

Multiplying by the millions

Planting a billion trees starts with producing a billion trees. Young trees of uniform size and quality were needed to ensure high survival and maximum early growth rates. In the 1970s FRI scientists developed equipment that greatly improved mass production of seedlings. Propagation techniques, such as cuttings and tissue culture, to mass-produce trees without using seed. Our forest nursery technology has spread around the world.

To ensure trees become properly established, shrubby weeds, such as broom, gorse and blackberry, must be controlled during the first few seasons of growth. Scientists conducted research on herbicides to find the safest, most cost-effective ways of controlling forest weeds.

Forest growth

Growth models predict how forests are likely to perform in a given place. These computer models use data collected from a permanent sample plot system. Growth rates of different tree species are regularly measured at around 12,500 plots. With this information, we are able to predict and regulate future wood production and how much carbon we are storing in our trees and forest soils.

One of the most important advances in New Zealand forestry research has been the development of planting, pruning and thinning systems for radiata pine to produce optimum growth and wood quality. For example, we established that early pruning of the lower branches from trees produces logs that are free from knots. The resulting ‘clearwood’ fetches a higher price from manufacturers of products such as furniture.

When crucial nutrients are lacking in the soil, they need to be added for trees to grow well. By studying nutrients in the soil, forestry researchers have identified fertilisers to correct the deficiencies in most regions of New Zealand.

Pests and diseases

With introduced trees came many new pests and diseases. From the 1920s the Forest Service was concerned that insect pests might come into the country on imported forest products and lobbied for effective inspection and quarantine systems. It also initiated research on forest insects and diseases.

The sirex wasp is an introduced pest that lays its eggs in pine trees, fatally weakening them. Its effects were understood in the early 1900s. Control is achieved by a combination of good forest management and the presence of natural enemies.

Using wood

Although radiata pine can be sawed, machined and treated easily, its properties vary from tree to tree, even when they are grown on the same site. Because of this, researchers have helped develop timber grading systems and building standards to ensure that the right wood is used for different purposes.

Wood has a high moisture content so it must be dried in large kilns before use. Drying must be carefully controlled to prevent warping and bending of the timber. Our research into the drying process leads the world. Breakthroughs include using high temperatures to dry wood as quickly as possible.

Preservative treatments to protect wood from insect attack and decay have been developed by chemical companies working with researchers. But, because public opinion has swung away from chemical preservatives, other treatments have been sought.

Managing forests from above

Drones are already changing the way we manage and monitor forests. Sophisticated cameras in the skies (or space!) allow us to detect diseases, weeds, water stress or nutrient imbalances on individual trees.

We have drones in the skies that are powerful enough, and clever enough, to drop a precise amount of fertiliser to a pine seedling or zap weeds with herbicide. Using soil maps, slope, aspect, weather reports and tree size, we will soon be able to precisely manage a tree differently from its neighbours.

All this is done remotely, safely and over difficult terrain. The forester of the future will spend less time slashing through blackberry and more time managing and creating insights from terabytes of data.