Forest Health News No. 315 - July 2023

Getting to know your basidio

Fungi are a highly diverse group of organisms that occupy many different ecosystems and niches, from the stumps of rotting logs to the walls of our digestive system. With an estimated three million undescribed species, fungi rank third among the eukaryotic kingdoms in terms of known species1. This vast and often unexplored diversity can make identification challenging. For biosecurity, it is important to provide diagnosticians with the tools, expertise, and knowledge to correctly identify the fungi they work with. The ability to identify fungi correctly is paramount for disease diagnostics, early detection, and eradication efforts.

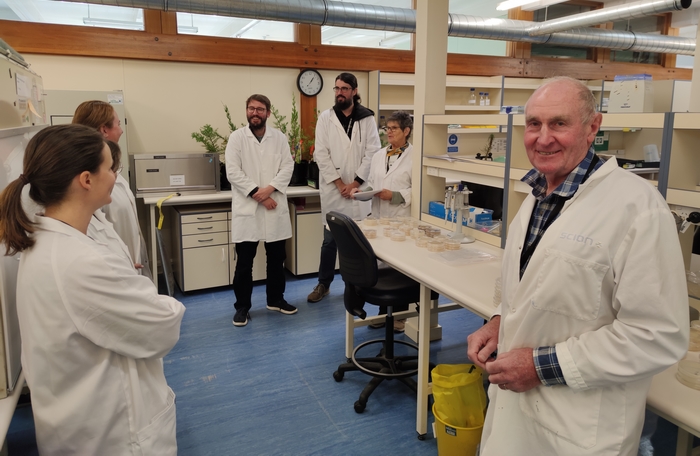

To ensure the continuous professional development of Scion’s diagnosticians, and to equip them with the current knowledge of plant pathogens, the Pathogen Diagnostics and Collections team has undertaken a series of workshops. These workshops are specifically designed to enhance and advance the diagnostic capabilities of the team for plant pathogenic fungi. Recently, a one-day workshop was conducted by Dr Ian Hood, a long-time, now semi-retired, forest pathologist at Scion, which focussed on the morphological identification of Basidiomycetes. This workshop coincided with the UN International Day of Plant Health on the 12th of May, rendering it timely and notable in its alignment with global efforts in plant health awareness.

The Basidiomycetes are a large group of fungi that include such diverse types as mushrooms and toadstools, crust and bracket fungi, rusts and smuts, puff balls and earthstars, coral and jelly fungi, and many others. Some are significant pathogens, such as Armillaria spp., Physisporinus vinctus, and Gloeopeniophorella sacrata, which cause root diseases in pines and other hosts, as well as numerous rust species, such as the introduced myrtle rust pathogen, Austropuccinia psidii. Many Basidiomycetes are important agents of wood decay in natural forests and in timber in service. Others are mycorrhizal, contributing to the diversity and function of natural vegetation, part of the “wood wide web”.

The day began with an introduction to Basidiomycetes to give context to the workshop. Distinguishing features, both macro- and microscopic, were illustrated and some of the published and online resources that help identification were shared. Some may ask, why is morphology still important in the molecular age? These days, genetic sequences and phylogenetic trees are now basic to fungal recognition and identification for taxonomy and diagnostics. But not all species are represented in universal databases and morphology still plays a key role. Fungi are more than just a barcode. They are living organisms, with shape, form, colour, physiology, behaviour, growth, and reproduction. So, the two methods are complementary. Nevertheless, morphological identification has its limitations, too, and these were also discussed.

The rest of the workshop was hands-on, in the laboratory. Participants studied a series of freshly collected fruitbodies of different Basidiomycete species. Some fungi were named and with these participants were tasked with recognising diagnostic features, such as setae, cystidia, clamp connections, and different types of hyphae and spores. Others were unlabelled and the challenge was to identify them using available identification keys and other resources. Later, participants worked on identifying a set of plate cultures of different Basidiomycete species isolated from substrates, such as wood, or from fruitbodies. Help was given as needed and the lab became a scene humming with feverish activity.

To add zest, the workshop was run as a competition. Participants were divided into two groups and points were awarded for recognition of key features and correct identifications. Marks were self-scored, honesty prevailed and at the end of the day the verdict was … a dead heat!

The objectives of the workshop were successfully achieved, namely that participants became more aware of identification procedures, developed further familiarity with macro- and microscopic characters, understood the scope (what can and can’t be achieved), and are now in a better position to continue the learning process themselves with diagnostic samples using available resources. All in all, the workshop was judged to be a resounding success.

Ian Hood and Darryl Herron

------

1 Hawksworth DL, Lücking R (2018) Fungal diversity revisited: 2.2 to 3.8 million species. In: Heitman J, Howlett BJ, Crous PW, Stukenbrock EH, James TY, Gow NAR (eds) The Fungal Kingdom. ASM Press, Washington, DC, pp. 79–95.

Update on the Granulate Ambrosia Beetle in Aotearoa New Zealand

The granulate ambrosia beetle (GAB), Xylosandrus crassiusculus, is a highly invasive and polyphagous beetle native to sub-tropical Asia. It has invaded every continent, except Antarctica, and attacks more than 100 species, mostly angiosperms, with rare reports from conifers. It was first confirmed in New Zealand in 2019, although has possibly been in the country longer. To our knowledge GAB is still confined to the Auckland region, but with no active monitoring program, we have no way of knowing its spread and current distribution. In a recent publication in Agriculture and Forest Entomology, Scion, the Ministry for Primary Industries (MPI), and international collaborators at the United States Department of Agriculture explored the phenology, trapping tactics, and known host range of GAB in New Zealand2 to understand the beetle’s behaviour.

To monitor GAB in Aotearoa, different species of woodbolts either unsoaked or soaked in ethanol, and three different types of ethanol lures with flight intercept traps were trialled. Generally, ethanol lured traps were more effective at catching GAB than ethanol soaked woodbolts. The two lures with the higher ethanol release rates were significantly more effective than the standard ethanol lure, showing the importance of optimising even general lures for specific species of interest.

Across the two years of monitoring, this study found that overwintering GAB adults emerged in spring (October - November), with the offspring (F1 generation) emerging in late December. There was also a small flight event in autumn (March – April), possibly a late F1 generation or a second generation.

A number of native host plants have been confirmed as GAB hosts, with more expected to be discovered over time. These include horoeka (Pseudopanax crassifolius), houpara (P. lessonii), whauwhaupaku (P. arboreus), karamu (Coprosma robusta), mahoe (Melicytus ramiflorus), kawakawa (Piper excelsum), kōhūhū (Pittosporum tenuifolium), and tī kouka (Cordyline australis). Most attacks on a native plant were found in the karamu. An interesting find was the attack on tī kouka, also known as cabbage tree; this is only the fourth reported find, globally, of GAB attacking a monocot.

The effects of climate change in Aotearoa are already being observed. Plants are being subjected to greater abiotic stresses, which is likely to lead to more impact from invasives pests, such as GAB. Scion, together with iwi partners, aim to investigate the impacts of GAB on native plants over the next few years. These studies are critical to inform policy, raise funding, and identify management strategies to limit the impact of this invasive beetle.

Andrew Pugh (Scion)

------

2 Sutherland, R., Meurisse, N., Pugh, A.R., Ranger, C.M., Reding, M.E., Kerr, J.L., Russell, J. and Withers, T.M. 2023. Phenological observations and trapping tactics for the granulate ambrosia beetle Xylosandrus crassiusculus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae, Scolytinae) in New Zealand. Agricultural and Forest Entomology.

Newsletter of the Scion Ecology and Environment team. Edited by Andrew Pugh and Darryl Herron, Scion. Contact: Andrew Pugh